Peter Doty, my 4-greats grandfather, had a sister,

Rebecca, who was the sister closest to him in age, just a bit younger. Rebecca married John Irish, son of Jesse Irish, and one of seven brothers who settled with their father in or around Tinmouth, Vermont, now Rutland County in 1768. This area was a hotbed of British activity, especially after the Battle of Ticonderoga in upstate New York, an American victory in early 1777. The British began to move southward and many Tinmouth residents packed up and moved south, too, to avoid this influx of the enemy. Others traveled to General Burgoyne's headquarters to ask for protection. John's father, Jesse, did so and was granted protection as long as he swore not to take up arms against the Tories and to just stay quietly at home. (After the war, Jesse was accused of aiding the British army, however, and his property was confiscated. Other brothers also were involved in transporting Loyalist citizens into Canada and safety after the war.)

Rebecca, who was the sister closest to him in age, just a bit younger. Rebecca married John Irish, son of Jesse Irish, and one of seven brothers who settled with their father in or around Tinmouth, Vermont, now Rutland County in 1768. This area was a hotbed of British activity, especially after the Battle of Ticonderoga in upstate New York, an American victory in early 1777. The British began to move southward and many Tinmouth residents packed up and moved south, too, to avoid this influx of the enemy. Others traveled to General Burgoyne's headquarters to ask for protection. John's father, Jesse, did so and was granted protection as long as he swore not to take up arms against the Tories and to just stay quietly at home. (After the war, Jesse was accused of aiding the British army, however, and his property was confiscated. Other brothers also were involved in transporting Loyalist citizens into Canada and safety after the war.)

Rebecca Doty, my gggg-aunt, married John Irish, born 21 September 1745, in 1772. Rebecca was a young teenager when she married the much older John, who was about 27. The couple moved to Tinmouth, Vermont, where John eventually purchased eighty acres of land from his brother, Jonathon, in May 1775. The farm was adjacent to the land one of his other brothers, William, and their houses were only a short distance apart. John and Rebecca had three children: Lucretia, born 1774; Joseph, born 1775; and Rhoda, born April 1777. One resource noted that John lived "by Quaker principles" which would mean that he did not want to involve himself in war or killing. In this interest, John, himself, traveled to British headquarters on July 27, 1777 and obtained protection for himself and his family...the very day that he was killed. One can be sure that the colonial soldiers kept a sharp eye on those under protection, lest they really be British spies or aiding the enemy in some way. And that is how John Irish apparently was looked upon by some - a man under suspicion, when perhaps he really just wanted to lead a peaceable life with his wife and young children.

|

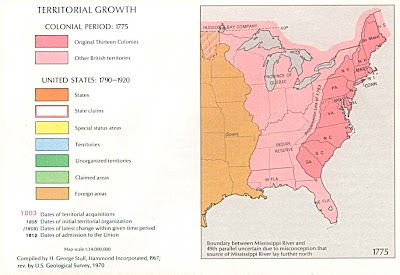

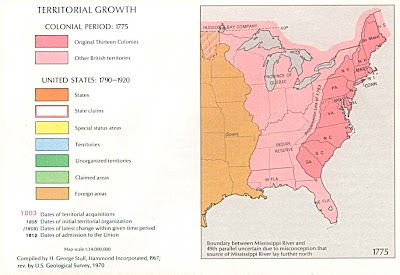

| Tinmouth was part of the New York colony at this time. |

|

|

|

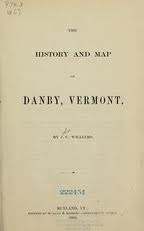

Several versions exist describing John's murder on July 27, 1777. One is a report given in the Rutland County, Vermont history published in 1886; a short description is given in Memoirs of Col.Seth Warner; and the last is an eyewitness account of Rebecca Doty Irish Stafford (she remarried) in the Danby, Vermont history (also published in the Rutland Herald in 1855), published in 1869. I am going to post them all and you can decide if the shooting was premeditated or self-defense.

Version 1: Rutland County, Vermont history (Syracuse, NY, Smith and Rann, Ed., 1886, Chapter XL - "History of Tinmouth")

"John Irish and his tragic fate merit some attention from the historian. He and his brother William lived in the north part of the town on adjoining farms, and built their houses but a little distance apart and near the road which ran parallel to the line fence between their farms. When the news of the surrender of Ticonderoga reached Tinmouth on the 1st of July, 1777, a great part of the inhabitants started southward into Arlington, Shaftsbury and Bennington. Those who did remain on their farms sought protection, as a rule, from Burgoyne. Among these were the two brothers Irish.

A little later the Council of Safety sent a scouting party consisting of Captain Ebenezer Allen, Lieutenant Isaac Clark, and John Train and Phineas Clough, private soldiers, into Tinmouth to learn what was going on among the 'Protectioners' and to reconnoiter a Tory camp in East Clarendon. These men were personal acquaintances of the Irish brothers.

When the party arrived in the west part of Tinmouth, they were informed that it was suspected the two brothers were about joining the Tories and that the shortest route to the Clarendon camp would pass their dwellings. They accordingly took that road. As they approached Irish's clearing, Allen directed Clough to give his gun to Train, go on and ask William Irish the nearest road to the Tory camp, at the same time telling him that he (Clough) had decided to go and join the Tories.

When Clough arrived at the house, he found both brothers and made the statement according to his orders. Clough was told that he must consider himself a prisoner; that they would see about his joining the Tories. William then directed John to take Clough home with him, and he would soon follow and help take care of him. John had an Indian tomahawk in his hand and told Clough to walk along with him; they walked on toward John's house, he with the uplifted tomahawk in his hand.

When Allen saw this from his place of concealment, he said to Train: 'We must get as near as we can to John's house without being discovered.' He and Train started by one path and Clark crawled along behind the brush fence, the three meeting near the house undiscovered. Here Allen gave directions that under no circumstances was either of them to fire until he did. He then stationed himself about two rods north of the path; Clark about the same distance south of it, and Train fifteen or twenty rods farther east, all being hidden behind trees.

They had not waited long until Clough stepped from the door and, after looking about, started for the woods. He had got partly over the fence when Irish came out, partly dressed, with a gun in one hand and a powder-horn in the other. He called out to Clough to stop or he would shoot him. While in the act of raising his gun, apparently to carry out the threat, Allen shot him through his left hand, knocking his gun from him. Irish then turned around so as to face Clark, who shot him through the heart.

The party, after killing Irish, went on to Clarendon, and after reconnoitering the Tory camp, returned to Arlington. It is perhaps, proper to state that different versions of this affair have been given, one of which is to the effect that Allen went to the dwelling place of Irish for the express purpose of killing him, but the details given above come down to us upon the authority of Judge Obadiah Noble, and probably should be given credence."

Seth Warner was a patriot and one of the Green Mountain Boys who fought bravely at Ticonderoga. In the Memoirs of Colonel Seth Warner , written by Daniel Chipman and published in 1848, the story of John Irish's death was told briefly this way: "John Irish settled on a farm afterwards owned by Judge Noble. Lt. Isaac Clark (of Herrick's regiment of rangers), in command of scouts sent out from Manchester, quietly surrounded John Irish's house and sent one of his men, named Clough, unarmed, to ask John Irish 'if he had any hostile designs against the Whigs.' Clough had been a neighbor of John Irish's, but on the evacuation of Ticonderoga, had moved off. 'They entered into a conversations which was continued for some time. At length, Clough began to suspect that Irish intended to detain him, as he was unarmed, and feeling unsafe, he walked with apparent unconcern out of the door, and turning the corner of the log house, out of sight of Irish, he set out on a run toward the scout. Clark, who was watching, saw this and instantly saw Irish chasing Clough with his gun, and perceiving that he intended to shoot him before he reached the woods, drew up his rifle and shot him dead upon the spot. This was represented by the Tories as a wanton murder, and many years afterwards, when Clark was in public life, and a prominent political partisan, some of his political opponents renewed the charge of murder against Clark, with many aggravating circumstances."

The account of her husband's death, as given by Rebecca Doty, was first published in the Rutland Herald newspaper by C. H. Congdon in 1855 and later in the Danby,Vermont history, published in 1869. Apparently, Congdon spoke with Rebecca Doty Irish Stafford and wrote the article based on that conversation and in response to an article by Judge Noble. Congdon stated, " I noticed a communication in your paper, over the signature of O. Noble

(Obadiah) , relative to incidents of the Revolution: and were it not for the fact that said communication had produced considerable excitement in this vicinity, I would gladly be silent. But whenever a matter of this nature is recorded, whether it be fact or tradition, unless refuted at the time, soon passes into historical truth. With due deference to the age and ability of Judge Noble, I shall proceed to narrate the circumstances as I understand them. I have had occasion during about twenty years, while collecting material for a work which I may hereafter publish, to consult the then (1777) wife of John Irish, now (1842), the widow Rebecca Stafford of South Wallingford. Of course, my information is traditional, but at the same time the most direct I think that can possibly be had of the 'Irish Affair.' The wife of John Irish was a strong, resolute woman and possessed a strong, retentive memory. She was an eye witness of the whole affair, and the following is her statement:

Rebecca began by telling how her husband, John, bought their farm from his brother, Jonathan on 20 May 1775. She had the deed in her possession and she provided a copy of it which was reproduced in the book. He loved his farm, improved upon it and lived there peaceably until the day of his death, she recounted. (History of Danby, Vermont, pp.172 - 174) Rebecca continued the story: " I have never heard it contradicted that the character of John Irish was without reproach. He, as well as many others of this vicinity, was a Quaker in principle, was quiet and unassuming. On the 24th of July, he went to Burgoyne's head-quarters at Skeensborough (now Whitehall) and procured protection papers and returned on the morning of 27th July, had previously been engaged in reaping wheat, he was now mowing, had mowed about an acre in the forenoon when Clough came to his house between 11 and 12 o'clock and enquired the way to Durham Bridge; wished Irish would direct him through the woods as he did not like to travel the road on account of spies. Irish told him to keep the road as the safest way.

Dinner being ready, Irish asked Clough to eat, but declined, but while Irish and his family were eating, sat partly in the door. After dinner, Irish put a pitchfork into the fire to bore a hole into a new handle and then laid down on the bed with his two eldest children. After dinner, Clough called for a drink of water, which Mrs. Irish gave to him, fresh from the spring; a few moments after she had fetched the water for him, while she was engaged in doing up the dinner dishes, all at once Clough started and ran out of the house in the direction of the spring. Mrs. Irish spoke to her husband, who immediately jumped up and followed Clough out of doors - at the same time his wife begged him not to leave the house - he advanced about three rods from the door, when Allen raised up from behind a maple log and shot Irish through the hand, severing his third and little finger from his hand, or nearly so. Clark then, in a rough manner, asked him if he wanted to take more prisoners. Irish answered that he should take or harm no man, and added, you have wounded me, upon which he held up his hand and Clark shot him through the heart. He turned, walked about a rod, and fell dead upon his face. When Clark and Allen shot him, he was not more than three or four feet from the muzzles of their guns - so near that the smoke rolled up on his breast as he turned around. After this, the men all disappeared in the woods. Mrs. Irish went immediately to Mr. William Irish's who was just putting on his clean clothes, being on Sunday. He said, 'Becca, you must take care of yourself, I cannot help you.' He immediately started off and did not return until six weeks afterwards. Mrs. Irish went home, but did not attempt to do anything with her husband (hoping that some neighbors would come in) until nearly dark when, no one coming, she, with Irish's two oldest children, Mary, 14 years, and Gibson, 12 years old, assisted her in getting him into the house; this they did by rolling him on a plank and drawing him along. She afterwards laid him out. When she returned from William Irish's, the children said to her that the men had gone and Papa was asleep. He was a man that would weigh over two hundred pounds, and it was with difficulty that she and the children got him into the house. He was buried the next day by Francis and David Matteson, Jesse Irish, the father of John, and a Scotchman by the name of Allen. A coffin was made by Francis Matteson from rough boards out of the chamber floor. The grave is about forty rods from where the house formerly stood, on a knoll; a mound and rough stones mark the spot to this day. The wife was not permitted to follow the body of her husband to the grave, as it was not thought prudent even for the men to perform the task, so perilous were the times. Scouting parties were out on both sides at this period. John Irish had three children, the oldest about three years, and the youngest only two months. Mrs. Irish did not know any of the men at that time; John Irish knew two of them; his wife had never heard him speak of only two. The party, after killing Irish, went to the widow Potter's, in the edge of Clarendon, and took dinner, stating that they had shot Irish; and here a few days after Mrs. Irish learned all their names, and also that they did not intend to kill John Irish, but that William Irish was the man they were after, as they had been offered 30 pounds for his head. The widow thus left, secured her hay and grain and also her flax, of which she had a fine lot. This was the situation we find her in when in the following November, Ernest Noble (the father of Judge Noble) notified her that she must leave, as he had purchased the place of the confiscating agent at Rutland, and that twelve days would be given her to leave in peace. She left within the twelve days - traveled on foot with her three children to Danby, a distance of seven miles, through the uninterrupted forests of the then wilderness country, rendered doubly gloomy by the fitful gusts and wails of a bleak November wind. Tears of anguish and regret no doube dimmed her eye and moistened her cheek, as she left her home and the grave of her husband and journeyed alone and unprotected through the wilderness to find protection for herself and children, among strangers, although her deceased husband's relatives. She had married John Irish when on his way from Nine Partners up the country, and consequently had no intimate acquaintances with his father's family. ( *Rebecca would have been about 18 years old at this time and her children, Joseph - about 5, and Lucretia, about 3. The baby, Rhoda, would have been only 3 or so months old. From this account, we learn that John Irish was apparently married before and perhaps his wife died, as the two children, Mary and Gibson, are called Irish' s children. It does not say that they left with Rebecca.)

[Note - Lucretia would have been around 5, with Joseph being around 3, and Rebecca would have been around 20 years old]

About three weeks after her husband was killed, and in her absence from the home, her house was pillaged of everything valuable - clothing, furniture, etc. All she ever found of the missing property was a valuable scarlet cloak, about three or four rods from the house, trampled into the mud and badly torn. Relics of plunder were met with years after, among some of the families of the western part of Tinmouth. It is stated by Judge Noble that the party took Irish's gun to the council of safety. This could not have been so, from circumstances I will relate: - About two weeks previous to the transaction above named, John Irish, hearing that all persons, irrespective of political sentiment, if found with arms, would be dealt with as enemies, and wishing to evade all trouble, he dismembered his fowling piece of its stock and lock. The lock was wrapped in tow and put in the bottom of his chest, and the stock and barrel, he took into a swamp west of the house. The former, he secreted under a hollow log, the latter in the same, and there the gun remained until the winter following Irish's death, when, Irish's wife, having no means to furnish her children with shoes, gave the gun to William Irish for the necessary articles. She told him where to find the gun and he went and recovered it and long had it in his possession. This party Judge Noble says were sent by the council of safety. Where the record of fact is to be found, I know not, but it is certain from documents in my possession, that they belonged to a class of men styled Cow Boys in those days; that their friends and families resided in Tinmouth, and that they went there of their own accord and their own responsibility.  |

| General Burgoyne |

After this affair, William Irish went to Burgoyne's camp, in about six weeks, or the same autumn, and resided in Danby, until the close of the war. Their property was confiscated. How? I believe that John Irish was never accused of being a Tory, was never tried as a Tory, and how his property could be confiscated, under the circumstances, was something that puzzled the most learned of the law subsequent to the peace of 1783. That it was confiscated, I do not contradict, but whether in accordance with the rules practiced at that time is a question. The best legal talent of the State decided more than thirty years ago that it was a fraudalent act, and that the heirs of John Irish could recover the property, but they, like their progenitor, were peaceable citizens and evaded litigation. Mr. Joseph Irish of South Wallingford was the only one I ever knew... Many offers were made him by legal men to recover the property free of expense to him, but being a Quaker, he always desisted and consequently, the Noble family have been left unmolested in the possession of the property. As regards the truth of the statement of the wife of John Irish, wherever she was known, her word was never doubted. She was a high spirited woman, with a temperment rather sanguine than otherwise, and her villifiers, with all their heroism, did not confront her. We will give an illustration: About six weeks after her husband was killed, one Noel Potter and another young man came to her house and demanded her husband's protection papers. In the words of the old lady, 'one with a drawn sword, and the other with an iron gunstick,' meaning a ramrod. She peremptorily refused, and at the same time, seizing the poker, ordered them out of the house. The precipitately withdrew and she was not again troubled with them. The foregoing is an account of this affair nearly word for word as the old lady gave it, and what motive she could have for falsifying the matter is left for others to judge. On the other hand, these men who committed the deed were conscious whether it was right or wrong. If right, posterity can judge of the merits; if wrong, their own consciences upbraided them. They are numbered with the past, both friend and foe, and far be it from me to characterize, now that they are gone. It is left for the reader to determine..." Rebecca married her second husband, Stutely Stafford, son of Thomas and Mary when she was twenty-one and a widow for about three years in 1780. They lived at Danby and later South Wallingford, Vermont, where the couple had at least six more children.

Story was found from the blog "At the Riverbend".

Rebecca, who was the sister closest to him in age, just a bit younger. Rebecca married John Irish, son of Jesse Irish, and one of seven brothers who settled with their father in or around Tinmouth, Vermont, now Rutland County in 1768. This area was a hotbed of British activity, especially after the Battle of Ticonderoga in upstate New York, an American victory in early 1777. The British began to move southward and many Tinmouth residents packed up and moved south, too, to avoid this influx of the enemy. Others traveled to General Burgoyne's headquarters to ask for protection. John's father, Jesse, did so and was granted protection as long as he swore not to take up arms against the Tories and to just stay quietly at home. (After the war, Jesse was accused of aiding the British army, however, and his property was confiscated. Other brothers also were involved in transporting Loyalist citizens into Canada and safety after the war.)

Rebecca, who was the sister closest to him in age, just a bit younger. Rebecca married John Irish, son of Jesse Irish, and one of seven brothers who settled with their father in or around Tinmouth, Vermont, now Rutland County in 1768. This area was a hotbed of British activity, especially after the Battle of Ticonderoga in upstate New York, an American victory in early 1777. The British began to move southward and many Tinmouth residents packed up and moved south, too, to avoid this influx of the enemy. Others traveled to General Burgoyne's headquarters to ask for protection. John's father, Jesse, did so and was granted protection as long as he swore not to take up arms against the Tories and to just stay quietly at home. (After the war, Jesse was accused of aiding the British army, however, and his property was confiscated. Other brothers also were involved in transporting Loyalist citizens into Canada and safety after the war.)